Intrigued by the hopes of the Faroe Islands since the 2019 Women’s World Cup UEFA qualification group draw that saw the preliminary qualifiers pitted against Germany, Iceland, Czechia and Slovenia I decided I had to go and see what was happening in the archipelago. From a look at the men’s side and a brief history of football on the islands to a trip to Tórshavn, a handful of interviews and a disappointing match against Slovenia, this is my Faroese football odyssey.

A stranger in a strange land

As someone who’s travelled over 60,000 miles since the start of 2016, it feels strange to note that I’m not an avid traveller, I’m never had a thirst for exploration, more content to stay where I’m comfortable. I’ve never had the need to be a cartographer, my geographical knowledge borders on shameful at the best of times, a train ride from Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Piccadilly all to alerted me to the proximity between the two. I only know where Nottingham is because I’ve been to Meadow Lane, the geography I do know whether it be England or abroad stems from football. I know towns and cities not for their historical significance or tourist attractions but for the local football teams.

With this in mind, it’s of little surprise that the first time I encountered the Faroe Islands it was in a football book, the archipelago somewhat unexpectedly the subject of the first chapter of Alex Bellos’ brilliant Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life. At the time of writing (2002) the Islands were home to a handful of Brazilian footballers, imported by Páll Guðlaugsson and Fábio Menezes. Whilst Faroese football has come a long way since, the picture painted by Bellos was one of a barely habitable land, his description of the islands evoking images of Arctic tundra. One anecdote from a player that of a match when the wind was so violent, the rain so torrential that the 50 or so fans who braved the match spent the whole time in their cars. An extreme climate that as the very antithesis of what the Brazilians were used to.

It wasn’t until I was on the bus to Stansted that I remembered Bellos’ words, a glance at my weather app showing a constant of 9°C for the duration of my trip. I instantly regretted not checking before I’d left the house, my jacket left to hang on the back of my bedroom door. As it turned out, it was an extremely mild 9°C and I found myself walking around Tórshavn with my sleeves permanently rolled up, bemused by the locals who wrapped themselves in winter coats; it was the height of Faroese summer. June the brightest and driest month of the year for the islands, the conditions as good as they were going to get for playing football.

On a list of 233 countries and independent territories, sorted by population, the Faroe Islands are the 22 smallest in the world, with a population hovering around the 50,000 mark. [Faroe Islands fun fact: you’re much more likely to encounter a sheep than another human on the islands, our woollen friends outnumbering people by a ratio of 2:1].

Just under 1,000km from Denmark, the self-governed islands remain a part of the Danish Kingdom (though gained home-rule 70 years ago) and can trace a human history back to the Irish, predating Viking colonisation. Their nearest neighbours can be found on the Shetland Island of Foula (320km away) and seem to value football as highly as their British cousins. Lying between Iceland and Norway, the country has much more Nordic sensibilities, Danish without being Danish.

Leg Day and an airport buried in mist

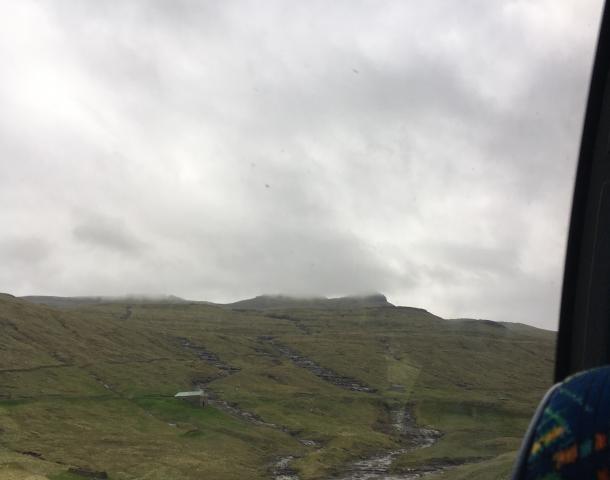

With a geography described by Wikipedia as “rugged and rocky with some low peaks; the coasts are mostly cliffs,” you can start to glean an idea of the islands but it’s not until you land that you realise you’re in for the Leg Day to end all leg days.

The runway at Vágar Airport appears as if from nowhere, the only airport on the islands, its history is militaristic, the site chosen because of its relative invisibility in the surrounding waters. As you start to descend through the mountains, your plane does little more than skim over the coastal waters, like a stone skipped out from Bergen, the runway suddenly under you.

From the airport you can get a shuttle bus to the capital, Tórshavn on the neighbouring island of Streymoy, the 50-minute drive giving you the perfect chance to cast your eye over the landscape. Rugged doesn’t begin to describe it, the 18 major islands are a series of mountains and hills with few plateaus, every inch of land that hasn’t been concreted or tarmacked, carpeted with grass. With over 250 average days of rain or snow a year, the grass remains well fed through the rising valleys with mirroring trails to break up the turf. The cracks in the greenery not man-made but rather the product of thousands of mini waterfalls, the rain having made its own paths over and over, the rocks uncovered by the constant streams.

It’s early June and the sun is shining through the blanket of grey sky that hangs over the archipelago, I won’t experience “night time” until I return to England, the summer a stark contrast to the winter. Thanks to the Gulf Stream the islands generally don’t have to deal with sub-zero temperatures, but the hours of daylight are scarce, December the darkest month of the year, January both the coldest and wettest. Though I spend the entire trip comfortable with my sleeves rolled up I have a constant breeze for company.

With all their home matches played at the national stadium of Tórsvøllur, I stayed an hours walk away. The floodlights that hang high over the pitch visible for most of the trek down to the stadium that also houses the football association, the FSF (Fótbóltssamband Føroya). Although football has been played on the islands since the late 1800’s, the FSF wasn’t founded until 1979, picking up from the defunct ÍSF, nine years later the association gained FIFA membership before joining UEFA the following year.

Almost a hundred years after Tvøroyrar Bóltfelag (the first football club of the islands) was founded, the FSF introduced artificial turf across the islands. The move has ensured reliable playing surfaces and has seen the popularity of the sport rise, and remains one of the most important developments in football on the archipelago. The work done by the FSF enough to improve conditions for players and bring more rigidity to tournaments, the league and youth levels paramount in furthering the national team. With the men’s U17’s notably having qualified for the 2017 Euros, the progress made is palpable, the team from last year the first ever to qualify for a final tournament.

Before the trip, the only piece of trivia I could dig out about the women’s team was that Bára Skaale Klakstein and daughter Eydvør Klakstein made the history books when they became the first ever parent-child pair to play together for their country.

A stalwart with a dismal history

A little research will fast throw up articles about imports to the Betri deildin men (Faroe Islands Premier League), men from all around the world – not just Brazil – have made the islands their home. Having arrived to play football, many take part-time jobs and settle on the islands, the unassuming beauty of the surroundings and uncomplicated friendliness of the locals enough to warm a stony heart. But whilst the archipelago remains a viable enough destination for male footballers, despite its low standing in European football, it’s a far different story for women.

The 1. deild kvinnur (women’s first division) exists exclusively for Faroese natives, the teams polarised between young and old, the heavy teenager drop-off doing little to improve the standard. Whilst there has been a recent change with EB/Streymur/Skála ending KÍ Klaksvík’s ironclad grip on the league, the Skála team keeping KÍ from the title for the first time in 17 years last season, it ends there.

Carving out their own history, KÍ is the only team to have qualified for sixteen UEFA Women’s Champions League (including when it was the UEFA Women’s Cup) seasons, although the team never reached the knock-outs they were the only ever-present in the qualifying stage. Having lost their crown, it was to be EB who attempted to navigate the preliminary round this month, a trip to Lithuania, hosts Gintra, NSA Sofia and Finnish side Honka all too much for the Faroese side to handle. EB suffering a similar fate to KÍ, the former champions only having ever finished third and fourth in their qualification groups [of four], a reminder of the level of football on the islands available at every turn.

Group 5

There is a popular internet meme that often gets trotted on out on Twitter during football drubbings, the picture is instantly recognisable as a screencap from The Simpsons. It features a young boy sobbing, “Stop, he’s already dead” as Homer (dressed as Krusty the Clown) beats The Krusty Burglar to a pulp. The image is one that instantly springs to mind when you read over the World Cup group qualification results for the Faroe Islands, the tiny Scandinavian nation that had conceded 37 goals in their first five matches.

From 8-0 at home to the Czech Republic at the start of qualifying to a second 8-0 four days later in Reykjavík, it was clear the team were in for a pummelling in their third outing, away to Germany. The Mechatronik Arena in the Baden-Württemberg village of Aspach witnessed the 11-0 win for the host, though the Kvinnulandsliðið can at least take some solace in the fact that wasn’t the largest margin in UEFA qualifying – that cherry went to Belgium who hit 12 past Moldova. A month later the Faroes were back in action against second-lowest ranked team in Group 5, Slovenia (at that time, FIFA ranking #58), a 5-0 loss watched by 200 fans in Ajdovščina.

The team did, however, show their improvements in their first qualifier of 2018 in what can warmly be described as a derby against Iceland. The hosts held out until the 37 minute, when Gunnhildur Yrsa Jónsdóttir put Stelpurnar Okkar up, a half-time result of 0-1, the Faroes’ best in qualifying. Three goals down with two minutes of regular time left, the home side were cruising towards their best result against a top side until the visitors struck twice before the whistle, once in the 89 minute and again four minutes into stoppage time.

That was the story so far when I embarked on a trip to the archipelago, keen to shed some light on the tiny nation and their footballing exploits. The Iceland game had seen the team take a step forward before collapsing against the might of the better side in the second half. Back at home two months later to the second-lowest ranked team in the group, Slovenia represented the Faroes’ best chance of taking something from qualification, maybe not a win but an elusive goal perhaps.

At the start of the group stage, 517 fans had turned out to watch the hosts concede eight in September with 367 pouring through the doors at Tórsvøllur for the Iceland match. The home side in the preliminary round of qualification, captain Rannvá Andreasen sees their hat-trick of wins in April 2017 as a turning point. Suggesting that inhabitants were barely aware that they had a women’s team before the matches in Tórshavn, a strong promotion campaign by the FSF enough to raise awareness.

Although just 195 people watched the Kvinnulandsliðið best Luxembourg, fifteen more fans turned up for their second match two days later; a narrow win over Montenegro. Their trio of wins completed in front of 1,450 fans three days afterwards, as they got the better of group favourites, Turkey. The match a palpable turning point for the team. The achievement one of the greatest in the history of the team.

From nine goals in three matches, the Faroes had gone five qualification games without a goal, the diminutive nation too often forced to defend their own box and unable to mount an attack on the opposition’s. However the Slovenia could change that.

Not enough warm bodies

The day before the match gave me a chance to talk to some of the players after their open training, the session was a paired down version of what you’d normally see. The goalkeepers kept themselves on one side of the pitch, the saves and here and there, the youngest of the trio called in by Pætur Clementsen looked the most promising. At 19, Anna S. Hansen has already been used three times in qualification, starting away against both Iceland and Slovenia as well as playing the second half in Aspach. Despite looking confident with Jóna Nicolajsen, Monika Biskopstø and the goalkeeping coach in the warm-up, the young ‘keeper looked considerably less assured in the mini match that the team played.

Condensing down on the pitch, Clementsen was keen to set and reset his players, directing them in different scenarios, again going back and talking to the group over and over. The team split almost in half, the subs, as well as Clementsen’s assistants, made up the opposition that his chosen side had to get past. The team were clumsy with the ball and fast run out of ideas. After training, the manager conceded that he didn’t want the team to overexert the day before a match, but from watching, it’s clear the side have an obvious ceiling.

Qualifying to the last 35 teams is clearly not something the team expected to do, plenty of respect for their opposition, building momentum over the week as Clementsen hoped, the side surpassed all expectation. The step up to the big leagues seemingly a step too far for the team. Though the failed qualification bid has pushed the squad further than before, the players now with individual training programmes and a clear idea of the level required to mix with the best.

Physically and mentally growing with each game, the team has evolved, the flurry of late goals scored by Iceland attributed more to a lack of concentration and mistakes begetting mistakes. Their loss to Germany wonderfully summarised by Ansy Sevdal as, “Like Barcelona playing some crappy team from I don’t know where so 11-0 is bad but when you consider the gap…” And what a gap it is.

The day of the match, the clouds broke over half of Streymoy, the sky blue on my descent back to Tórsvøllur, the stadium still covered by a blanket of light grey, the match as lacking of light for the hosts.

One of the few players in the team who is neither a teen nor in her 30’s, Ansy seemed relatively full of energy after their loss to Slovenia. Relaxed in English, she beamed with pride when she pointed out that her team (EB) finally displaced KÍ, a little gleefully admitting that it’s far more enjoyable beat a team rather than to just join them. The young Sevdal comes from good stock, having been playing alongside older sister Heidi on the pitch, the attacker a multiple winner of Faroese women’s footballer of the year. Unstoppable in 1. deild kvinnur, the elder Sevdal stood out for all the right reasons in the loss, her tireless runs and thirst in attack giving the crowd something to cheer about, the 29-year-old a class apart.

The loss was frustrating to watch, the team almost overawed by the match, a first half that was best forgotten but the team found themselves after the break, teammates linking and a threat posed in attack. The introduction of Milja Simonsen in the 65 minute gave the team a new dimension, the 21-year-old pairing well with older Sevdal; Zala Meršnik’s clean sheet under threat. Ultimately the hosts couldn’t find that magic moment, Slovenia simply better as individuals as well as a team, the basics executed well where the hosts too frequently slipped up.

Captive audience

Described as almost, a tradition for families to go out on Sundays and watch matches by Sevdal, it is clear that the universal language of football is spoken across the archipelago. Playing for 30 years, the last 17 of which have been as a member of the national team, Andreasen has seen the developments made in her career but admits the drop off at about 17-years-old leaves teams unbalanced. The problem echoed by her coach, the team is polarised between young and old, too many of the younger players letting football fall beside the way, studies, others sports and travel to Denmark all playing their part. With a push to give a greater platform to women’s football on the islands – and plans by the FSF to increase participation numbers at grassroots – the tide is slowly turning around the islands. Yet for the league, it’s a familiar story, attendances of 200 for top games commonplace, but “Mostly it’s boyfriends and family” in the crowds.

Despite the drop-off, participation remains huge in the Faroes as FSF president Christian Andreasen can attest having told UEFA, “Interest in football in the Faroe Islands is huge. We have a population of 50,000 and 5,000 active football players - 10% of the population; that might be a record.” During the same visit to Nyon, Andreasen shared his view for the future, “Our goal is to maintain this interest, provide better facilities and try to make our mark in international football.”

Realistically, that mark in women’s football is a long way off and as noted by Clementsen there is a lack of stability for the team, who will have to go through another preliminary round ahead of the draw for Euro 2021 qualification. Failing to progress will leave the team without a clear idea of how to spend two years, playing friendlies but not able to pit themselves against the best, evolving each match. But with a strong crop of young players coming through who are nothing but motivated to represent their country, the coach believes the future is bright and as he says, “We put things in perspective, we live on a tiny island with 50,000 inhabitants, so I think we’re doing okay.”

For players like the younger Sevdal, the opportunity to share the pitch with some of the best in women’s football is a rare treat, the midfielder conceding that she “Almost wants to applaud,” thinking, “I want to play like that, they’re awesome!”

Small island, small budget

For Clementsen and his team, a trip to Chomutov five days after the loss at Tórsvøllur brought about the Faroes’ first goal of the group stage, Simonsen introduced off of the bench (again) to score a late consolation. The goal ending a 629 minute drought for Kvinnulandsliðið, the goal not enough to overturn the four they had already conceded, but a rainbow after a weathered storm.

Back home in London, a city whose population of over 8.7million is over 175 times that of the entire archipelago of the Faroes, I celebrated Simonsen’s goal with a happy fist-pump, the team deserving of something for their efforts. The trip had opened my eyes and gone some way to explaining football on the islands, as well as helping me understand the natives, the friendliness, their love for football and hopes of progressing. Young talents like Hansen and Simonsen enough hope for the future, stalwarts like Andreasen providing the backbone with Heidi Sevdal the magic maker for the team, key foundations in place.

It’s no surprise that Iceland is the smallest nation to qualify for a World Cup, it’s hard to reach such a high level when it’s not just your population that is so small but the budget you have for football is as diminutive. It’s hard to imagine a smaller nation or micronation making a major tournament anytime soon unless they do as teams like Northern Ireland do and look for those with lineage who might have grown up in a larger country and been privy to better facilities.

When Jayne Ludlow talked about Wales being a small country with a small talent pool she might not have realised how fortunate she is, not just for coming from a comparatively large population but being next door to a burgeoning league. For the Faroese, Denmark is the logical choice though it comes with its own perils, the 3fLiga not known for its strength. In recent times the Danish league has been mined by Damallsvenskan and to a lesser extent Toppserien. However, if players were to go to Denmark, they’d replenish the pool, hopefully starting their own evolutionary chain to progress to Sweden and beyond, perpetuating their own footballing diaspora.

But for now, it’s small steps taken on the islands, tireless work of those like Clementsen at the FSF, those growing crowds for matches at Tórsvøllur and the grit of those who pull on the shirt and battle for ninety minutes, the future in their hands.