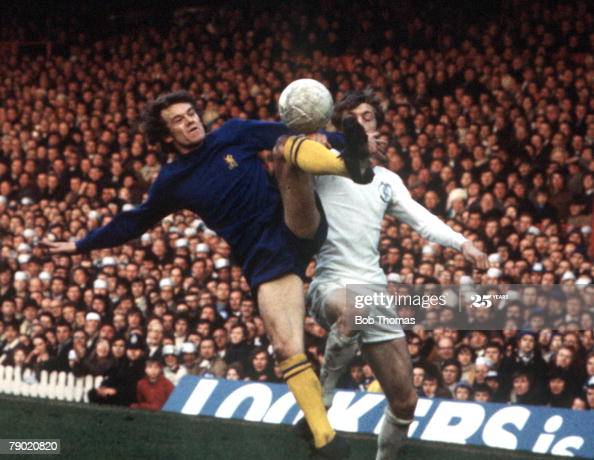

In 1970, 28 million people watched Chelsea and Leeds United attempt to win their first ever FA Cup.

At the time, its significance was probably a more likely indicator of how loved and appreciated the world's oldest national football competition was back then.

Few paid attention to the intense rivalry that was born when a flying David Webb header cannoned into the back of the net in the 104th minute of the replay to win it for the Blues.

On the pitch, the two teams shared broadly similar philosophies. It is perhaps fair to say that kicking your opponent was as important as kicking the football. Of course, it was a different era and current Premier League referee Michael Oliver famously said he would have issued a total of 11 red cards that day. Guidance from coaches regarding extensions of the leg did not specify what the foot should make contact with.

In later years, the rivalry escaped the confines of the pitch and erupted on the terraces. Both clubs had notoriously troublesome firms and - even as modern football brings back a general level of calm - chants about the other from either set of supporters are less than complimentary.

Arguably, it is now a rivalry of the past that dissipated upon Leeds' relegation from the top flight in 2004. The occasional chant but may have set off a few sparks, but the fire could not burn without the oxygen regular matches provided. The two teams have only met once since, a League Cup match at Elland Road in 2012 that resulted in a 5-1 thrashing from the Blues. Full-blooded thriller it was not.

Only a few rivalries in football that are not local can exist without regular meetings and competitive ones at that. Even the hatred between Manchester United and Liverpool, two colossi of the English game, has at times felt stale. Just once in the last 30 years have both been going for the title at the same time.

Roy Keane and Patrick Viera once stared each other down in the tunnels at Old Trafford and Highbury. This conflict no longer has such a combative feeling once both the Gunners and United slipped down the table.

Rivalries that are not local need an extra edge and Chelsea vs Leeds often did. It was far more complicated than just bitterness that arose as a result of one of the biggest ever cup finals.

Could the rivalry spark up again now that Leeds have finally secured their return to one of Europe's most prestigious leagues? Or is it buried in the memories of older fans?

For some guidance on the issue, VAVEL spoke to Chelsea's official historian, Rick Glanvill.

-

The North/South divide

For the millions that watched the likes of Peter Bonetti, Ron Harris and Peter Osgood face off against Billy Bremner, Eddie Gray and Jack Charlton, the difference could not have been clearer.

The brash and uncompromising Don Revie headed a Leeds United moulded in his own image and represented the working class north of England.

'Dirty Leeds' was the tag they were often branded with, perhaps a little unfairly, but it stuck.

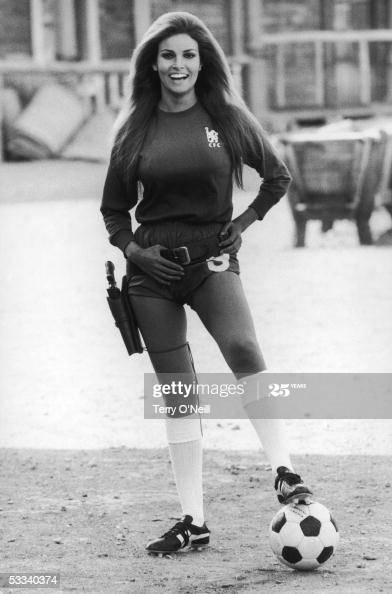

Chelsea on the other hand, were one of the more stylish clubs around. West London and the Kings Road in the 1960's attracted the rich and famous. Even film star Raquel Welch donned the Chelsea strip, guided by club legend Osgood.

Worlds apart then, but the truth is now that the city of Leeds has hit a different trend. Vastly popular with students, it is now the UK's fastest growing city according to its own council. It is probably not a breeding ground for class conflict anymore.

Glanvill said: "I’ve seen the city [Leeds] change incredibly since the 1970's, definitely for the better. It’s diverse and high-tech rather than cloth cap and cribbage these days. Obviously, though, Chelsea still has the stardust: the best part of the greatest city in the world.

"The stereotypes that fed into the rivalry are largely irrelevant."

-

Bielsa, Lampard and 'spygate'

Leeds fans have not forgotten the events of last season when a spat between then Derby County manager Frank Lampard and Peacocks boss Marcelo Bielsa broke out over allegations of spying.

Said allegation, which involved an affiliation of Bielsa supposedly spying on Derby's training ahead of a fixture between the two, ultimately ended in a £200,000 fine for Leeds.

The feelings between the two parties were further soured when the Rams ended Leeds' playoff campaign in a stunning win at Elland Road that involved the likes of Mason Mount and Fikayo Tomori.

The post-match celebrations demonstrated that the events in the preceding months had not been forgotten.

Now that Lampard is back at the Blues, it is the closest reference point younger Leeds fans now have. Should tensions arise again, it will undoubtedly be a clash of a different kind.

"Thankfully, most of the fans who were fighting each other back then are now past it," remarked the Chelsea historian.

"Of course, it depends on how the matches go. The media will probably try to hype the build-up with Bielsa versus Lampard and the spygate angle, but it’s not as if Johnny Giles and Eddie McCreadie are still around to kick bits off each other on the field, and Revie is spouting off about ’soft southerners’ every week."

-

A new generation

Leeds fans tryna force a rivalry with Chelsea....

— łez (@ftbllez) July 18, 2020

"The other thing to note is that a club's support base seems far less localised than in the past. Changes in society have made it okay to follow a team based thousands of miles away, or even fly to see them in the flesh," said Glanville.

Chelsea's phenomenal success since the late 1990's, as well as social media, has meant that the club is followed worldwide. Rightly or wrongly, it is true that the Blues' trophy haul and growth has brought them more airtime, meaning that they can increase their influence on fans across different continents.

.jpg)

Most of this new generation of supporters remember do not remember the days when the Blues went without silverware, the period that coincided with the height of the distaste shown to Leeds.

It is different for older fans of both teams. In a 2019 poll, Leeds fans listed Manchester United as their foremost rivals and Chelsea second.

The Yorkshire club's stay in the second tier has meant that Leeds are not at the forefront of the Blues' vitriol, but competitive fixtures may just bring it back.

Glanvill noted: "We've only played Leeds once in 16 years. It’s the intensity of meaningful matches that builds rivalries – look at Chelsea [and] Liverpool between 2003 and 2010, and how that sparked friction. With Leeds, a generation of Blues has grown up with them barely a talking point.

"Obviously older supporters’ ears prick up when we hear their fans still singing ‘fetch yer father’s gun’, and everyone likes a 'we all hate Leeds and Leeds and Leeds’ every now and then, but they have felt like remnants of a bygone age. Until now."

There could be animosity upon Leeds' return, but it is more likely that it will be because of the dislike between the two coaches, rather than more traditional differences that cause it.

Older fans will be quick to remind younger generations, though.