The current mood around Chelsea is one of cautious excitement. After beating their nemesis Wolfsburg in the quarter-final of the UEFA Women’s Champions League, the Blues now head into a semi-final meeting with Bayern Munich. As such, they are one step closer to realising Emma Hayes’ ‘nine-year project’.

However, the quarter-finals did seemingly reveal a chink in their armour - one that has many questioning the team’s mental resolve to finish the season strongly. There are many questions that need to be answered to truly determine whether there are faults, and if so, does Hayes have the resources to adapt and change things.

Are Chelsea better equipped at playing a certain system? Does Pernille Harder fit the current setup? Or are there players who could be better utilised to improve the side? This analysis will try to answer these questions and more.

-

Systems, roles and an evolution

With the additions to the squad, Hayes turned her attention into trying to fit in arguably the world’s best player in Harder. Now with Sam Kerr, Fran Kirby, Harder and Bethany England to choose from, Hayes needed to find a system that allowed as many of her attacking talents to play at once without sacrificing their quality.

Thus entered the return of the 4-2-3-1 formation which saw Harder integrated into her favoured Number 10 position. Though the 4-4-2 is still a highly used formation, they’ve reverted to a 4-2-3-1 more often and added the 4-3-1-2 variant too.

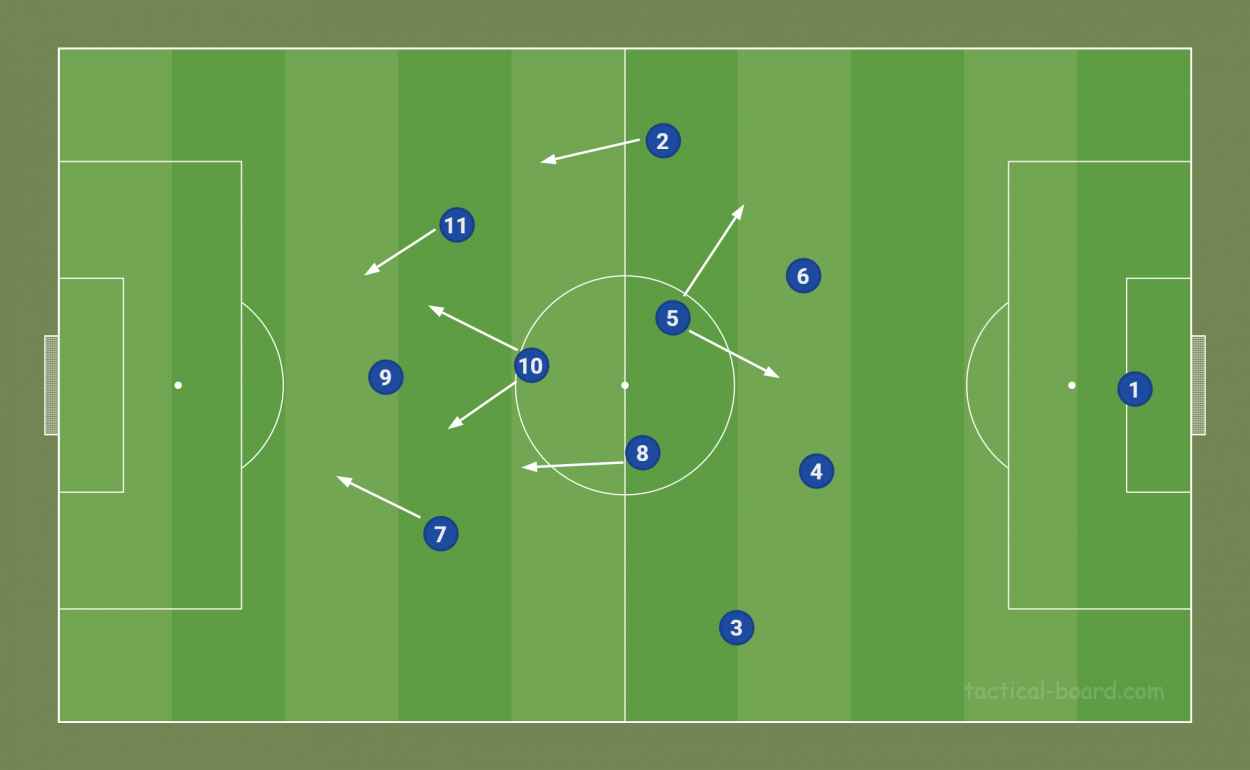

Tactically, the 4-2-3-1 system is often played when you have players who prefer to cut inside from the wide areas to overload the centre of the pitch. It’s a system focused on creating overloads and superiorities across the pitch. One of the reasons for its popularity is the flexible approach it offers, giving the team balance in both defence and attack.

A core double-pivot offers you a base to work from and enables the attacking three to interchange and link up with the centre-forward. Additionally, the full-backs play an integral role in creating width and overlapping runs.

However, the more you think about it, the less it becomes about the formation but rather the philosophy and ideology behind each role and how it all integrates together. The new systems are slight variances from one another, with only the 4-4-2 offering a real difference.

Even then, you’d have to play Guro Reiten and Erin Cuthbert to offer some natural width. The basic premise is to facilitate an attacking midfielder whilst still playing to the other key players’ strengths.

The evolution to the new system seemed to move away from a more counter-attacking style to a much more positional and possession-based system given the excellent ball carriers they had. The graphic illustrates Chelsea in possession and how Hayes wants them to set up in this 4-2-3-1.

Melanie Leupolz and Ji so-Yun in midfield changed the dynamic of how Chelsea would build up and offered a lot more quality passing and carrying. Though Sophie Ingle is a proficient ball retainer and passer, her German teammate provides a more attacking threat with slightly more mobile offering and similar passing abilities.

At Bayern Munich, she excelled in her positional play and made late runs into the box which coincides with the demands of their new possession-based style.

The stats back the change as we see Chelsea averaged 3.43 counter-attacks with 37.6% ending in shots in 2019/20, compared to the current season numbers of 2.57 with 41.6% ending in shots. So while they might be more efficient at counter-attacks, their frequency has certainly reduced drastically.

The front four had set starting positions but their constant movement makes it hard to pinpoint their actual positions. Harder would take up the attacking midfield position while Kerr and England rotated as central strikers, sometimes even starting together. The right flank was taken up by Kirby when fit whilst the left flank was taken by Cuthbert or Reiten.

However, Hayes has experimented by playing Kerr in a wider position which meant both Cuthbert and Reiten were left out of the side and England started as the central striker. This prompted a more positional approach given the number of rotations possible with the players at hand.

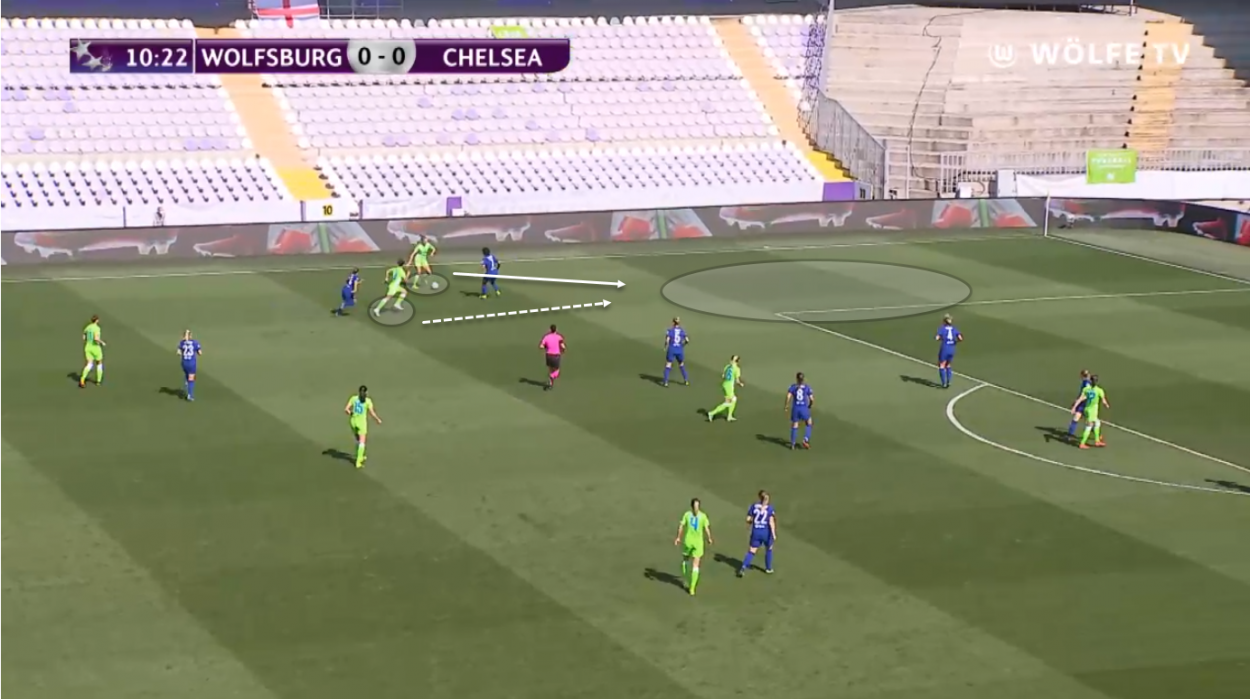

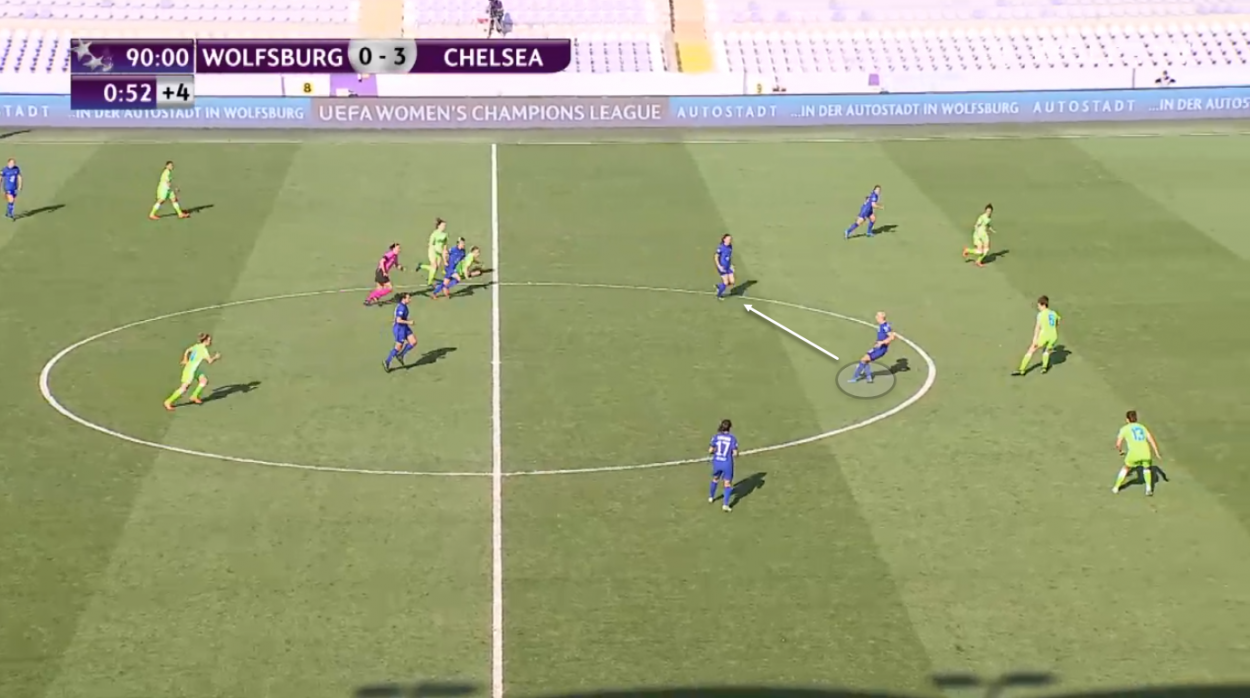

Kerr would often drift into central positions, whether it be deeper to link play or in the attacking third to create a give-and-go option as the above example suggests. Equally, both Harder and England are occupying central positions in the box in anticipation of a cross.

What’s notable is that you could put playing all three players together to generate a different attacking approach. What are Harder, Kerr, and Kirby good at? Their abilities to rotate and move positions seamlessly whilst playing quick, transitive football which means Chelsea pose a different threat going forwards, and that’s more effective against low block sides.

The idea and concept are similar in the 4-3-1-2 with a couple of tweaks where width is totally reliant on the full-backs, but with the ones at Chelsea not pushing up as high, this poses a slight issue going forward.

Chelsea have never really relied on the full-backs as true attacking sources, rather as a set of supporting players who possess a strong defensive base. For the better part of two seasons now, Jonna Andersson and Maren Mjelde have been the first choice full-backs; both of whom are not natural attacking full-backs.

The wide defenders are usually positioned high up the pitch but will initially be deep enough to receive passes from the central defenders.

However, once an opening is found, whether it be a long-ranged pass or a more central passing option through Leupolz, you will often find the ball-side full-back pushing up if they’re near the attacking move.

They won’t be the source of crosses but instead as supporting bodies in the final third, tasked to follow the moves.

Nevertheless, what we’ve seen across the quarter-final is Chelsea getting the balance of their full-backs right. Often they can be left isolated against quick wingers and teams with some tactical nuance can expose that with simple 2 v 1 overloads and move in behind. The example below from the second leg against Wolfsburg shows just that.

Jess Carter is pulled out towards Fridolina Rolfö and tries to block her passing options but Felicitas Rauch makes an early and quick enough run behind Carter to expose the area in behind. This also calls into the full-backs’ 1 v 1 defending abilities into question, what with their best defender in Mjelde out injured.

This approach also presents its own issues in breaking down defences which Chelsea will face against tougher opposition. If England was fit to play against Wolfsburg, there was a good chance we’d have seen her start for both her pressing abilities and direct style of play.

Kerr can play that role but each one of Chelsea’s forwards has their own technical proficiencies and serves a tactical purpose for each game. What can be perceived as a weakness could very well be an experiment gone wrong or adaptation not working to its best.

Using Ji and Leupolz as the double-pivot can work if Chelsea are expected to hold the majority of possession because of their passing and carrying abilities. Though, as we saw against Wolfsburg, they were outrun and bossed in midfield against the hardworking combination of Alexandra Popp, Lena Oberdorf, and Ingrid Engen.

The introduction of Ingle and Cuthbert for the second leg gave them a bit more defensive solidarity, allowing Leupolz more freedom and the full-backs more cover. Cuthbert’s energy and box-to-box role were key in breaking down Wolfsburg’s attacks.

Taking this example against Aston Villa, notice the number of Chelsea players in midfield against their two banks of four. With the creativity they have, Chelsea often find a way through quick, incisive passing exchanges.

The pass from Ji to Leupolz broke Villa’s mid-block and exposed the back four to three Chelsea players breaking forward. The quick pass went down the left and within seconds, two to three Chelsea players enter the box, including Harder who drifts in behind the defenders to calculate her run.

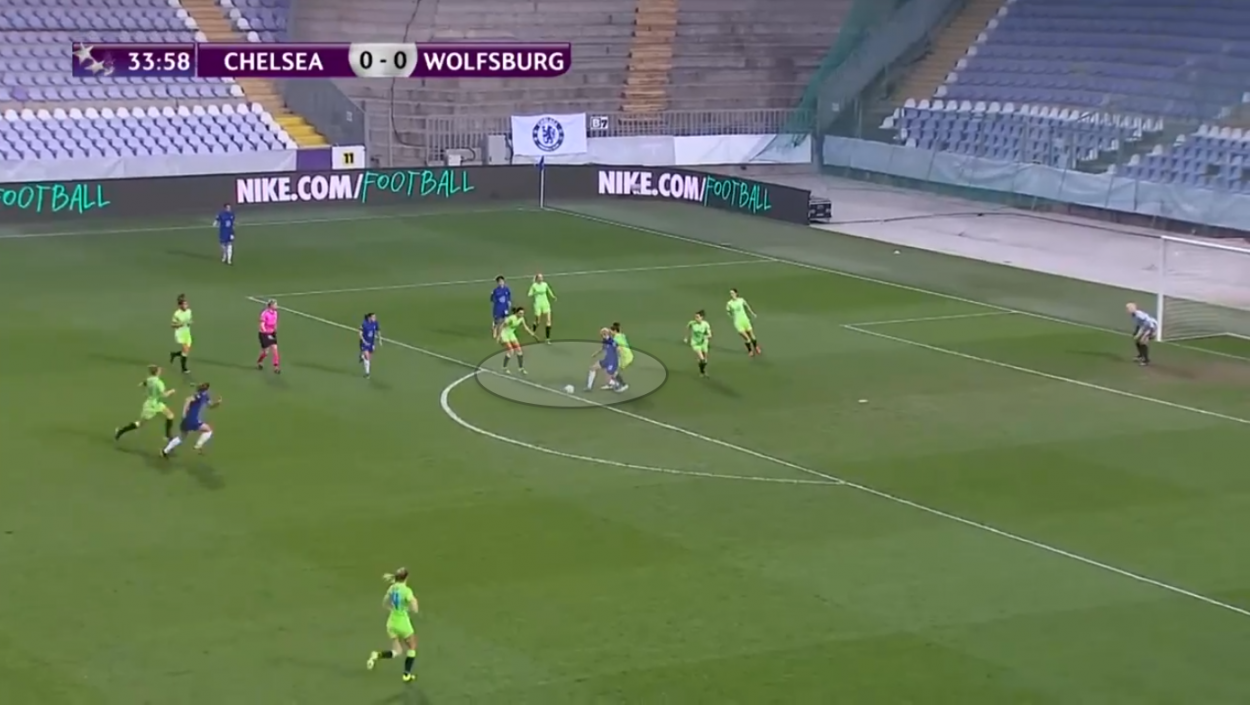

The problems with this approach to interchangeable play arise when teams defend compactly and aggressively even close to their own box. Stephan Lerch nullified Chelsea’s approach by deploying a more aggressive pressing approach in his team’s own half through Engen and Oberdorf.

They played a mid-block holding a strong 4-2-3-1 shape when Chelsea were building out from the back and positioned themselves in between Chelsea’s players.

Wherever the ball moved, Wolfsburg moved across as a team whilst maintaining a man-marking pressing system. This enabled them to force the ball carriers to pass it quickly and force mistakes in passing between the backline.

Here is a passage of play where Chelsea start down the left flank but when they drive into the middle, they are surrounded by Wolfsburg players, eager to close them down and suffocate the space.

In the second leg when Chelsea switched to a more counter-attacking system, they were able to score twice and though they invited more pressure than they needed to, the Blues seemed more defensively solid. The only time they gave away chances was when the full-backs were out of position, giving Wolfsburg space in the wide areas to attack.

-

Number 10 Role

Perhaps the most intriguing position of the current Chelsea setup is the role of the Number 10. Chelsea has probably found this position to be the most complex yet technically what is supposed to be the most effective to integrate into the current setup because of the profile of the player that arrived over the summer in Harder.

In a nutshell, the attacking midfield position is used as both an on-the-ball attacking weapon by making late runs, but also as a method of creating space being positioned between the lines.

A depiction of this role was once occupied by the second striker in Chelsea’s 4-4-2 but playing with an attacking midfielder means there are somewhat different requirements in this role.

When build-up comes through the wide areas, the attacking midfielder’s sole focus is to find space in the box through well-timed runs. Not only does this add to the numbers in the box to create overloads, but it pulls players out of position to create space for the others around the box.

When build-up is more central, the ‘10’ needs to roam in between the lines and create space by moving players out of position to allow the two strikers extra room to manoeuvre through.

Many a time you’ll see the attacking midfielder drop into a deeper midfield position to collect the ball, lay it off, and move across the final third into space. The example below illustrates this.

Harder drops deep into midfield to lay off a pass to Reiten and makes a run for the box.

Here she is initially positioned between the two defenders but while their focus is on the ball, Harder wants to slip in behind the full-back (#13) to gain a blindsided run.

Hayes’ thought process behind creating this role was to both facilitate Harder but also leverage the strengths of the players around her. It’s easy to forget that Harder has always had teams built around her as the centrepiece and while the formation has been changed to accommodate and integrate the Dane, we have to expect there to be a period of adaptation to the system, as well as the club and country.

At Wolfsburg, she was a trequartista, a player capable of controlling play with great vision and creativity. They look to dissect the final third and dictate attacks, with defending pretty much going out of the window.

Her defensive numbers have increased compared to last season where she averaged 4.18 defensive duels per 90 minutes, 1.61 interceptions per 90, and 3.86 recoveries per 90 in 2019/20. Her numbers have jumped up to 6.85 defensive duels per 90, 2.39 interceptions per 90, and 4.83 recoveries per 90.

One scenario that has yet to played out to its fullest is seeing England replace Kerr in this 4-3-1-2 system as the central striker alongside Kirby. What she offers is much more of an 'off-the-shoulder' type presence and one which could invite Harder to be on the ball more than she is now.

England thrives off running in behind and getting Harder to supply England with Kirby could be another method of adaptation and approach to empowering the Danish forward.

A few short months ago, Harder was dubbed the best player in the WSL, and though we have seen only flashes of brilliance, that isn’t necessarily down to a flaw in the system but the inconsistency of the player herself to produce at the level the system and manager needs.

Against Wolfsburg, you would have heard Hayes ask Harder to press consistently as did Kirby against Birmingham City. This is becoming a repeated theme which can only result in the player’s probable distaste for the ‘dirty work’, but if she is to succeed then there has to be an element of blind faith.

Kerr initially struggled for months and doubts were raised on her ability to translate her NWSL form to England but at the time of writing, she has had 17 goals and 5 assists from 19 games, leading the goal-scoring charts in the WSL. Hayes talked about Kerr adapting her off-the-ball play as evidenced by the aforementioned figures.

-

More to come

To put all of this into context, it’s not so much that Chelsea are struggling tactically or that Hayes is unsure of her best team, but rather it is getting her team to understand and adapt to the evolution of her style of playing that now includes Harder.

Chelsea are still playing swashbuckling football and if they're able to send the Wolves back to their den whilst playing 'poorly' then surely this is a side that is a scarier proposition when fully functioning, surely?

In retrospect, it's easy to lay blame at the first sight of faltering but given Hayes track record, she has earned the right to be given time and deeper analysis needs to be done before passing judgement.

Chelsea’s win against Birmingham isn’t going to cast away doubts, but it just goes to show how even a rotated side can equally carry out the manager’s ask with a big win. Bayern Munich couldn't come soon enough.